By David Colker, Senior Press & Communications Strategist, Communications and Media Advocacy

JUNE 1, 2023 – 10:30AM

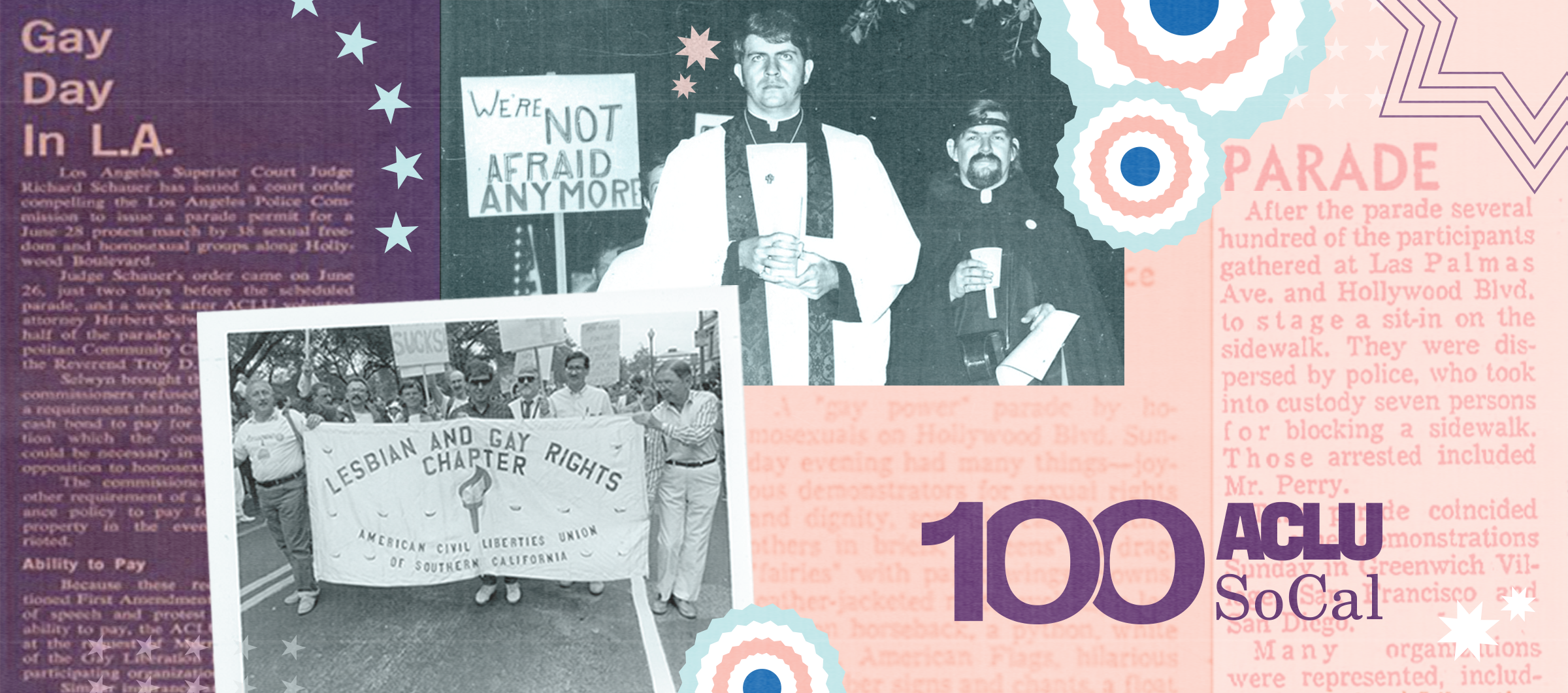

The first LGBTQ Pride march in Los Angeles — featuring floats, serious protest signs, hilarious protest signs, costumes, chants, motorcyclists, pets, and a drag depiction of a police raid on a gay bar — headed down Hollywood Boulevard on June 28, 1970.

But it almost didn’t happen.

The Los Angeles Police Commission, which issued parade permits, had imposed severe financial and other conditions on the pride parade organizers that other groups didn’t have to meet. The commissioners were not only openly hostile to the parade organizers, but they also made fun of them.

That’s when the organizers called the ACLU of Southern California.

“These ridiculous conditions make it impossible to hold a parade,” attorney Herb Selwyn, who took the case for the ACLU SoCal, told the Los Angeles Times. “They violate these law-abiding citizens’ right to peacefully assemble.”

Selwyn was no stranger to LGBTQ civil rights matters. In the 1950s, he helped incorporate one of the first U.S. LGBTQ organizations, the Mattachine Society, and he wrote a “Know Your Rights” summary that could be put on a card and consulted in case of police harassment.

In 1968, backed by the ACLU SoCal, he represented two men who had been arrested during a violent police raid on the Black Cat gay bar in Silver Lake during a New Year’s celebration.

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the Black Cat case, but the argument eventually came to be widely accepted.

Before Selwyn represented the parade organizers, had had a disastrous meeting with the police commission to request the permit. “We had decided to not use the word homosexual,” said Troy Perry, 82, the last surviving organizer of the march, speaking from his home in Los Angeles. They had applied for the permit in the name of the Metropolitan Community Church, not mentioning that the church, founded by Perry, was created as a place for LGBTQ people to worship openly.

“They asked, ‘What kind of a church is that?’” Perry said. “And I answered, ‘a Christian church.’” But the questions kept coming and Perry was getting angry.

“About the fourth time they asked, I said, ‘We represent the homosexual community of Los Angeles!’ Well, they all looked like they were having heart attacks.”

This was at a time when the LAPD, run by archly homophobic police Chief Ed Davis, regularly raided gay bars and used entrapment tactics to make arrests. Several gay men died in police custody, and many others were hurt when officers beat them. Davis, who equated LGBTQ identities with criminal behavior, told the commission, “We would be ill-advised to discommode the people to have a burglars’ or robbers’ parade or homosexuals’ parade from a legal standpoint.”

Parade organizer Morris Kight struck back. “This is a colossal piece of ignorance,” he said, quoted in the L.A. Times, “that goes to the root of misunderstanding in the community.”

But Davis essentially won out. The commission voted 4-to-1 to require the organizers post a cash bond and pay for a large liability insurance policy. “They said it was to pay for businesses that were going to be damaged from all the rocks and bricks people would throw at us,” Perry said. “It was like how the Nazis treated Jews — make them pay for the damage that other people did.”

There was no way for the organizers to raise the funds needed to meet the commission’s demands. “We didn’t have $100 among us,” Perry said.

Kight, who died in 2003, had the idea of calling the ACLU SoCal, which takes civil rights and social justice cases at no charge to clients.

Selwyn, who died in 2016, took the matter back to the police commission. He told a Los Angeles Times reporter that the commission’s requirement of “a $1 million liability insurance policy and payment of a $1,500 fee for police services” particularly violated parade organizers’ rights.

He made it clear to the commission that the ACLU SoCal would take the matter to court if the conditions imposed on the permit were not eliminated. The commission dropped some but not all of its prejudicial conditions, and Selwyn made good on his promise.

Just days before the parade was scheduled to happen, he argued the case before Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Richard Schauer. The judge came down decisively for the parade organizers.

“Homosexuals are also citizens,” Judge Schauer noted, citing the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression. He ordered the commission to drop its conditions.

Perry was ecstatic. “No one believed we could win in court, but the ACLU won it for us!” he said. “Now we had to put on a parade.”

Amid much applause, laughter, and joyous tears, the parade came off as scheduled. There were some catcalls by homophobes, but none of the violence Chief Davis and the commissioners had so assuredly predicted.

There was also, among the thousands of spectators, a stark reminder of the fear LGBTQ people had of being publicly identified. “I’d never seen so many men wearing hats drawn down and dark sunglasses,” Perry said.

But the parade itself — and all that it took to put it on, including the battle with the police commission — was for many, Perry believes, a turning point.

“It was the first major event I feel that showed people we could be ourselves in public,” he said.

The next year’s parade, he said, was twice as big.

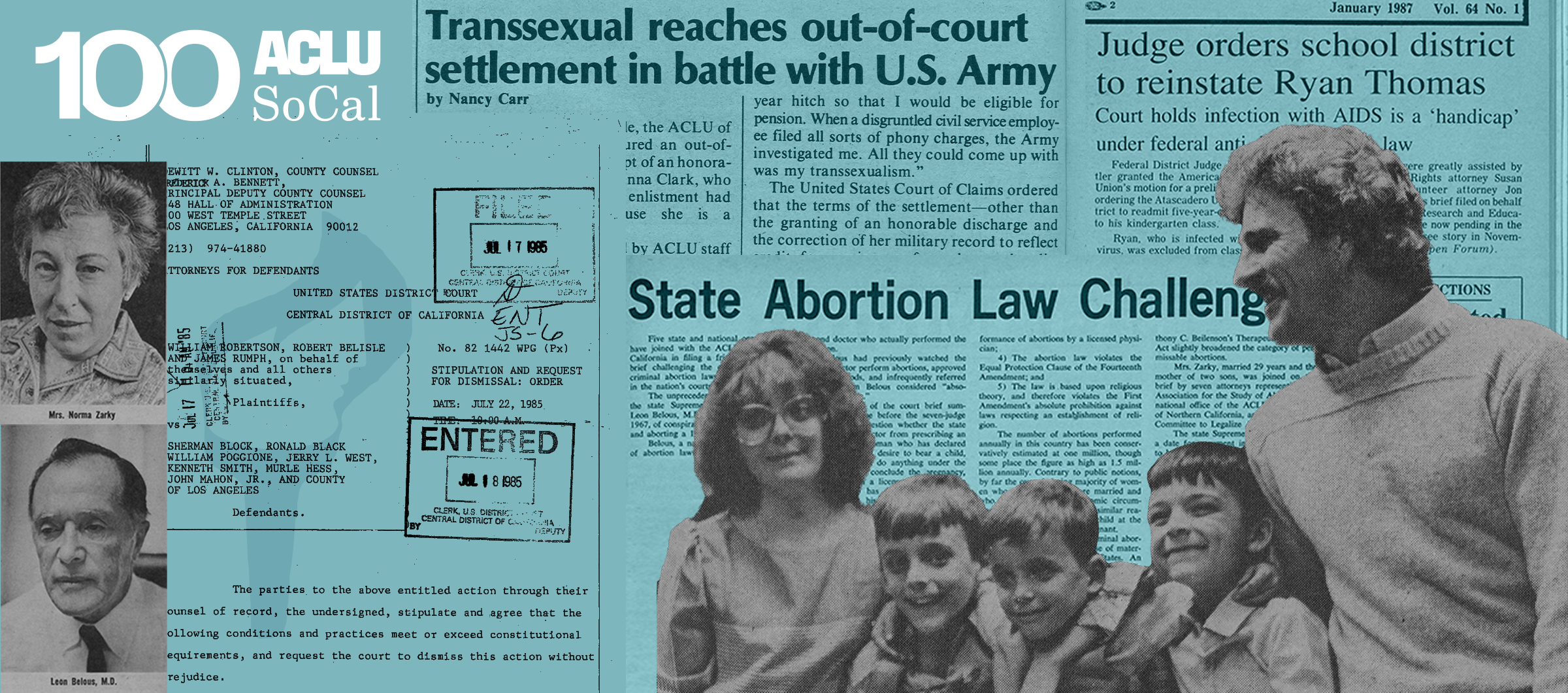

This article is part of the ACLU SoCal’s centennial series, exploring the affiliate’s long and evolving work and impact in the southland. The series lifts historic milestones and facts documented in the “Open Forum,” the ACLU SoCal’s newsletter published from 1924 to 2004. This year, in partnership with the California Historical Society, the ACLU SoCal has published and digitized the “Open Forum” in its entirety. Explore the archives and read more about how the ACLU SoCal fought for the first L.A. Pride Parade.